I've been really busy with travel, conducting and judging, premieres of new pieces AND writing new commissioned pieces for next season. Yes, it's good to be busy- it keeps me away from having the time to join a street gang or take up macrame.

I will try to get back to more regular blogging soon. In the meantime here is a great story on conductor Mariss Jansons from "The Observor"- and note especially down toward the end of the article where he speaks of where the magic, meaning, and real music resides:

Mariss Jansons: 'The notes are just signs. You have to go behind them'

Mariss

Jansons is regarded by many as the best conductor in the world. On the

eve of a visit to the UK with the Amsterdam Concertgebouw he talks

about his Latvian roots, his heart attack on the podium, and why he's

never satisfied with his performance.

‘It's

not so difficult to beat in time’: Mariss Jansons conducting the Vienna

Philharmonic's 2012 new year concert. Photograph: Herbert

Neubauer/Corbis

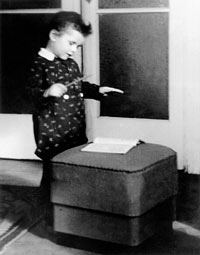

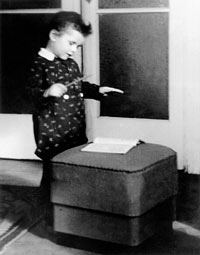

Shoulders

down, elbows relaxed, forearms doing the work: the stance is perfect

for a conductor. The left hand is shaping the sound; the right, neat

and commanding, clasps the baton. Look more closely. Is it in fact a

pencil? There's something odd about the score lying open on a satin

footstool, with no sign of an orchestra. And that sprigged smock is

hardly standard maestro uniform, still habitually white tie and tails.

Even the more sartorially adventurous tend not to sport knickerbockers.

Mariss Jansons was three years old when the photo was taken. He is now one of the top conductors in the world, inhabiting that tiny pinnacle of Mount Olympus where a handful of others – Barenboim, Rattle, Harnoncourt, Haitink – jostle at any one time. The cowlick of hair, broad cheekbones, deep-set eyes and boyishly tilted nose are identical to those of the freshly scrubbed, wan but vigorous 69-year-old sitting opposite me in the salon of Lucerne's grandest hotel. His tawny corduroy jacket is neat in the European manner, his navy drill trousers, like his pale blue shirt, crisply pressed. Only the eyes, a clear grey-blue, are a little crinkled, animated by the grins and frowns which are part of his expressive nature.

Mariss Jansons was three years old when the photo was taken. He is now one of the top conductors in the world, inhabiting that tiny pinnacle of Mount Olympus where a handful of others – Barenboim, Rattle, Harnoncourt, Haitink – jostle at any one time. The cowlick of hair, broad cheekbones, deep-set eyes and boyishly tilted nose are identical to those of the freshly scrubbed, wan but vigorous 69-year-old sitting opposite me in the salon of Lucerne's grandest hotel. His tawny corduroy jacket is neat in the European manner, his navy drill trousers, like his pale blue shirt, crisply pressed. Only the eyes, a clear grey-blue, are a little crinkled, animated by the grins and frowns which are part of his expressive nature.

Mariss Jansons playing conductor, aged 3. Photograph: courtesy Mariss Jansons/Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra

Nominating a "best conductor" is a futile activity, but many music connoisseurs, if pushed, would name the Latvian-born Jansons, who is chief conductor both of Amsterdam's Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra and the Munich-based Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra. Both ensembles made the top 10 in a 2008 Gramophone list of the world's top 20 orchestras, giving Jansons the limelight as the only conductor to appear twice in the list. He will be in the UK next week to conduct the hallowed Concertgebouw as part of their international residency at the Barbican.

Born in Nazi-occupied Riga in 1943, Jansons was steeped in music from the cradle. His mother was Jewish, forced into hiding at the time of his birth having lost family members in the Riga ghetto. Unexpectedly, he is Lutheran, like his father. "My mother knew it was dangerous for me to be Jewish. In Soviet Riga you took your father's culture and heritage… " The sentence peters out. He is not comfortable with these dark recollections.

Does he remember that infant snap being taken, or the music he was "conducting" at the time? "No, I have no idea," he chuckles. "But I was certainly already interested. My father was a conductor and my mother was a soprano. I spent so much of my early childhood in the opera house at Riga where they worked. They didn't like leaving me at home with a nanny. I soon knew all the ballets from memory and many operas. And it was the start of my fantasy: to play [violin] in someone's theatre orchestra, or maybe to dance and of course to conduct."

He had a toy theatre which has become part of the Jansons mythology. An only child, he played with it for hours on end, staging his own performances. "I'd make instruments out of two sticks, singing my way through music I'd heard. But I was already in effect studying conducting techniques, watching my father or his colleagues even when I was very small." An incipient talent for football, spotted by a local trainer when he was around six, was soon quashed by his parents: young Mariss would become a musician and that was the end of the matter.

The first disruption to this absorbing way of life occurred when the family moved to the USSR in 1956 when Jansons was 13. His father, Arvids Jansons, had been appointed assistant conductor to the powerful and influential Yevgeny Mravinsky at the Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra. Thrown into a new culture at an awkward age, as well as having to negotiate the highly competitive Soviet education system, the teenager was sent to study violin and conducting at the Leningrad Conservatory. He found the experience traumatic.

"It wasn't so easy. It was, perhaps, one of the greatest difficulties of my life, even though people were warm and welcoming. I was thrust into a higher level of teaching, in a new language which I didn't understand. My father was a famous conductor. I had to make my own mark. I had to be serious and disciplined and work very hard."

Did he then, and does he now, feel in any sense an outsider? In the course of a working day he switches from Russian to German to English, none of them his native tongue. He has two passports – Russian and Latvian. His wife Irina is Russian. "None of this matters to me. I am a cosmopolitan. I work mainly in Holland, Germany and Switzerland. My home is in St Petersburg. I wish countries could borrow the best from one another. I admire, for example, the discipline and respect you find in Japan."

While hardly an advocate for the old Soviet regime, he still appreciates certain aspects. "The educational standards were so incredibly high. It saddens me now that Russia is so much about money and following your own pleasure." Surely his religious belief, a powerful element in his psychological makeup, was discouraged? "How could they stop what was inside me? I did not attend religious ceremonies but my belief was and remains strong. They'd have had to kill me to get it out of me."

After spending a few years as a professional violinist, Jansons worked as a conductor in Leningrad, where he took over his father's old job and spent a while "getting out from under his shadow". He moved to the Oslo Philharmonic as music director in 1979, where he stayed more than two decades but fell out over the lack of a good concert hall (a battle he is now fighting, with minimal success, in Munich). The Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra followed (1997-2004), but he was never in his element there and found the jet lag exhausting.

Now he works only with an elite four orchestras: his own ensembles in Amsterdam and Munich, plus the Berlin Philharmonic and the Vienna Philharmonic. He refuses to guest conduct with other orchestras. He doesn't, as far as I know, advertise expensive watches. You will not find him acting as a public ambassador for world peace or education like Daniel Barenboim – though naturally he cares about these issues – or attracting the headlines with quite the same certainty as Simon Rattle or Claudio Abbado. Jansons prefers a less showy existence. His close relationship with his musicians is referred to by both sides in terms of a love affair.

"Orchestra have to work with many conductors," Jansons observes. "They want variety. I must always be working at the highest level myself, because that is what is expected of me." This ruthless dedication is one of the reasons his artistry is so valued.

Another is his physical vulnerability. He has a worrying medical history. His father died in Manchester from a heart attack on the podium while conducting the Hallé in 1984. Jansons too, almost unbelievably, suffered the same experience in 1997 but miraculously survived: he had reached the closing pages of La bohème in Oslo when he collapsed with heart failure. He took two years to make a full recovery. His health remains a source of anxiety, especially for his wife and doctors, but he considers himself fit.

"The heart attack was a very dramatic situation," he agrees, with typical understatement. Players told him later that he was still trying to conduct Puccini's score even as he slumped to the floor. "And I suppose I probably was, though I do not remember."

Now fitted with a defibrillator and closely monitored, he tries to live healthily, relax more, eat a good diet and take more holidays. "But for every human being such an event is shocking. You cannot suddenly stop being nervous and anxious about things. You just do your best to manage." His timetable remains hectic. Little wonder he is said to travel with a medicine chest rattling with pills for any eventuality.

"I try not to exaggerate the problem. Sometimes I overwork. The conducting itself is OK. But when you're a chief conductor there is an enormous amount of administration and meetings and other concerns. I am rehearsing and that's already hard work, but I must also be involved in auditions, in deciding programmes and soloists."

Jansons has been with the Concertgebouw since 2002 and is only the sixth chief conductor in the history of the orchestra, which celebrates its 125th anniversary next year. One of his predecessors, Bernard Haitink, 83, will conduct a concert at the Barbican residency. Jansons's own will be devoted to Richard Strauss, whose music is closely associated with the orchestra through Willem Mengelberg, chief conductor from 1895 to 1945. He shaped the Amsterdam sound, and was a close associate of Strauss. Does this give the players a special "Strauss" sound or is that an exaggeration?

"It's difficult to explain, and very interesting, but there is a sort of miracle that happens when they play Strauss, or Mahler too. You can say 'but no one played with Mengelberg. The musicians are international, the playing habits quite different from a century ago, so how can it be?' But there is some sort of spirit, some psychological moment of recognition, and I think you can say that it is a tradition being passed on."

Jan Raes, chief executive of the RCO since 2008 and a former orchestral musician, describes Jansons as "a perpetual student. He's always well prepared. He uses every second of rehearsals efficiently, with no long stories. He gives them everything he has. He is never laid back. All the players feel the pressure to work hard at the highest level, but they are always respectful too."

"Yes, Mariss is mercilessly hard on himself, and uncompromising," agrees Peter Meisel, a spokesman from Jansons's other orchestra, the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra. "After a concert he will get the recording [for private orchestral use] and that same night, after the post-concert event when it is already late, he will listen to it all the way through to see what was good, what was bad." And if he finds errors? "He blames himself."

"My task is to correct," Jansons says. "You must blame yourself if something goes wrong." What happens when he conducts the same works with his two orchestras? Do they ever sound the same? "No completely, totally different! Each great orchestra still has an individual sound, thank God," Jansons laughs. He makes the comparison with having two children (he himself has one, a daughter from his first marriage, who works as a rehearsal pianist at the Mariinsky theatre): "You love them equally and you appreciate and negotiate their idiosyncrasies."

He doesn't mind comparing his orchestras out loud, either. The Bavarians are "in the best sense German, with a big sound and tremendous explosive excitement." By contrast the august Concertgebouw is "transparent, capable of great delicacy, polished, never forced".

In addition to the Strauss concert at the Barbican, Jansons will deliver a lecture on the mysterious art of conducting. "Not everyone can take the baton. The conductor doesn't produce the sound, of course. If a principal woodwind or brass player cannot play a passage, it's tragic. It's not so difficult to beat in time." The virtuosic musicians he works with will play the notes whatever the conductor does, or fails to do.

"So you have to study deeply and express your wishes. The notes are just signs. You have to go behind them and see what your fantasy tells you. But how do you express that through sound? If you think of the technical aspects of conducting as being on the ground floor of a big building, then 20 floors up you are beginning perhaps to get the sound you want."

He checks his watch. He must go. His conducting duties at Lucerne's Easter festival are completed. Is he travelling home to St Petersburg for a rest? "No, I'm off to hear Bernard Haitink rehearsing with my orchestra and I must not be late. I want to see what he does, and how they respond. He is such a wonderful Bruckner conductor, you see. I might learn something."

The very notion, coming from one of the finest Bruckner conductors of our era, seems ridiculous but is, one must concede, just possible.

No comments:

Post a Comment